And Students of Mass Media Can Help Imagine the Future

In the last year, numerous reports in media and technology press have indicated that streaming services like Netflix, Hulu, and Max (formerly HBO Max) face unprecedented challenges. Consumer appear increasingly frustrated by rising prices, subscription plans that change frequently, and hit-or-miss content. Yet these companies are only experiencing what many media businesses — especially cable TV companies — have navigated historically after they have disrupted the status quo of entertainment distribution and experienced a period of explosive growth.

The media category of “streaming” is capacious, referring simply to “the continuous transmission of audio or video files from a server to a client” according to an explainer from network services company Cloudflare. But while the term therefore might technically encompass a user’s “live” stream via Instagram or Twitch or a video call on Zoom, it is arguably most commonly used to refer to the entertainment distribution services that deliver access to a portfolio of professionally-produced multimedia content.

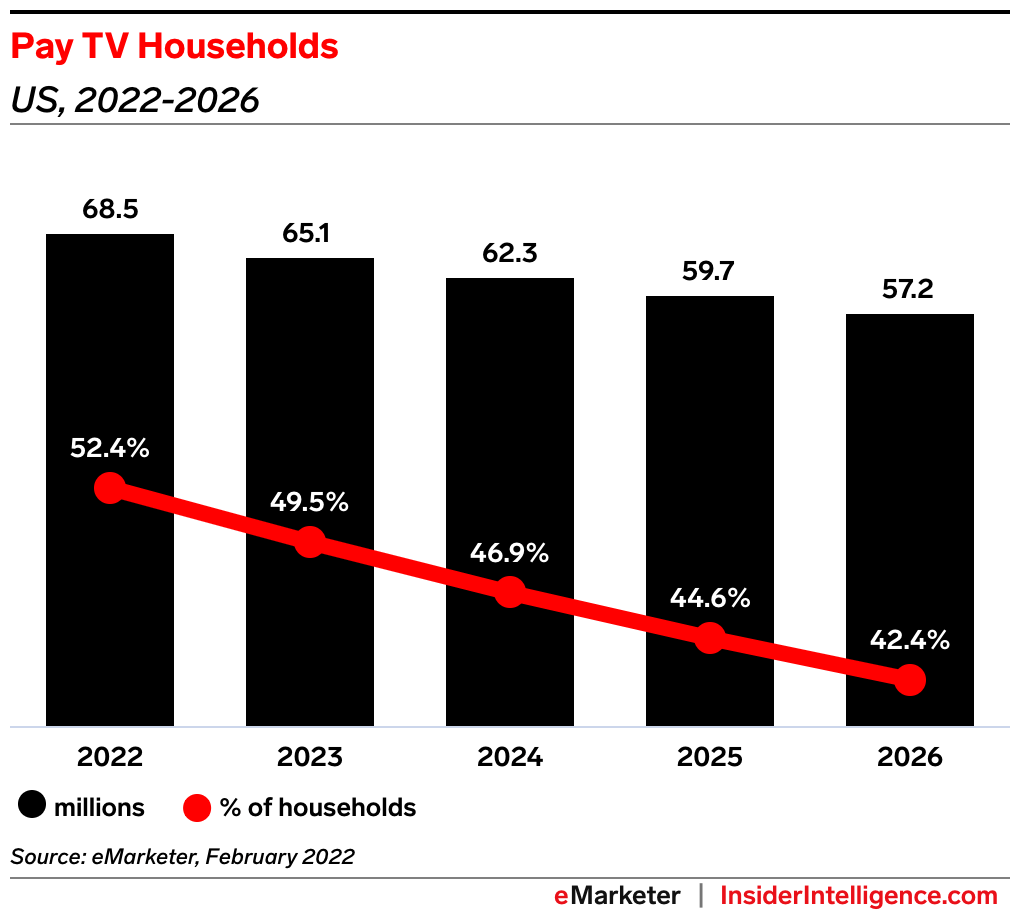

Netflix is sometimes cast as the catalyst for the “streaming revolution,” pivoting from its DVD-by-mail service to subscription-based streaming (though not without hiccups) starting in 2007. A critical mass of consumers have “cut the cord” from cable service and migrated to the ever-multiplying streaming platforms since then, and in many ways, streaming is the new “mass media.” The market research and consulting company SkyQuest valued the total streaming video on demand (SVOD) market size at $97 billion by the end of 2022, and predicted growth to $175 billion by 2031.

While the cord-cutting trend is unlikely to reverse itself, industry observers have nonetheless noted troubling trends for the major SVOD companies more recently. One of the biggest factors is referred to as “churn,” meaning that new streaming subscribers are often mostly or entirely offset by the cancellations of existing subscribers. As reported in Quartz, the analytics firm Antenna, for instance, notes that while streaming services in the aggregate gained almost 165 million new subscribers in 2023, they lost about 140 million. According to Antenna’s latest data, this net growth of around 25 million is down considerably from net subscriptions of around 41 and 46 million for 2022 and 2021, respectively.

According to some analysts, it is streaming platform policies themselves that are to blame for the uptick in churn. More than anything, companies keep raising prices while sometimes also cutting features and limiting the number of devices on which services can be shared. As Techdirt‘s Karl Bode put it pointedly, the increase in churn should not be a surprise when the companies like Max are “imposing bottomless price hikes and new annoying restrictions — all while simultaneously cutting corners on product quality in a bid to give Wall Street that sweet, impossible, unlimited, quarterly growth it demands.”

This kind of trajectory has played out before in media history. It mirrors a typical arc in which companies prioritize subscriber or user growth at the expense of all other metrics in order to establish dominance in a market and to maximize their valuation. Quoted in a recent piece in the technology news publication Ars Technica, an executive from Max’s parent company WBD seemed to indicate that this had indeed been the mentality:

[T]hese products are priced way too low. And I think this was partly the capital market-fueled phase of land grabbing. You couldn’t lose enough money and couldn’t grow subscribers fast enough. I think that’s behind us.”

Looking forward, then, Bode sees the approach increasingly being taken by Max and others — “where you consistently charge more money for fewer features and less quality” — as a parallel with “what ultimately happened in both U.S. telecom and cable TV.” Given his decades of experience as a media journalist, Bode predicts that we will soon reach a point “where the industry will start making it difficult to cancel service” in order to try to mitigate the churn.

What it also means is that streaming companies large and small also now have an opportunity to consider what features actually appeal to audiences and how they might create more sustainable business models that will retain a core user base rather than chasing infinite growth. These are some of the same questions that students consider in learning about the evolution of mass media. There are a number of theories of media reception and effects that can help conceptualize the role(s) that media play(s) in people’s lives, such as the “uses and gratifications” theory that students learn in any course on mass communication. From recent audience research, it also turns out that price is not necessarily the variable that consumers value at the expense of all others. As the research company AmDocs put it in their recent report called “The New Streamer,” in fact, “cost is not everything, and instead, “consumers say original content is their most important consideration.”

Any critical juncture in the evolution of a media industry — even if it looks like a crisis — can be an exciting moment to forge new directions. To take an adjacent example, former Google public policy leader Tim Hwang predicts in his book Subprime Attention Crisis that advertising might cease to be a viable foundation for media business models in the not-too-distant future, which would theoretically mean that media consumers would have to “pay” for media products in some other way than viewing ads. It is difficult to envision, but perhaps this could open up new ways for those who do the work of creating the media to make a living and reach an audience with a product that the audience is happy to pay a little bit for. Given the analyses of the situation in the SVOD market discussed here, the young people studying and making media right now would seem well positioned to brainstorm and participate in such re-imaginations.